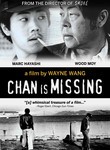

REVIEW: CHAN IS MISSING

Buy | Rent | Book

Buy | Rent | BookPreface: This was originally written for the 2001 catalog for the New York Asian American Int'l Film Festival sponsored by Asian Cinevision. It was also reprinted for my AsianAvenue.com column. I have made minor edits to it for republishing here (the bulk of this essay is just as I originally wrote it in 2001). Given the mission of the site, expect that this will not be the last word on Chan ever written.

THE REVIEW (in full after jump).

Early into Wayne Wang’s CHAN IS MISSING, gumshoe detective Jo (Wood Moy) and his sidekick Steve (Marc Hayashi) wander into a Manilatown senior center in search of their wayward colleague, Chan Hung. The movie takes a brief pause here as Wang shoots old manongs dancing to the Mexican bolero, “Sabor a Mi.” One shot lingers on an elderly man staring at the camera, collapsing the third wall with his steady gaze. The entire scenes only consumes a minute or so and then Jo and Steve are back on Chan’s trail, but the beauty of the moment lingers on.

I never had a chance to see CHAN IS MISSING when it hit the theatres – in 1982 I would have been all of ten, living in a white, San Diego suburb, without a glimmer of an Asian American consciousness. Instead, I was introduced to the movie a dozen years later, the way most of my younger peers become familiar with it – through a film class where CHAN IS MISSING sits on top of a tiny canon of “important” Asian American works. From the very onset, we’re taught that the movie is significant because, as Jessica Hagedorn puts it, “it was a first”. The first Asian American feature narrative to gain mainstream accolades, the first to get wider distribution, the first to launch Wayne Wang’s own storied career.

But CHAN IS MISSING always meant more to me than just for its pioneering status. As a teacher, film festival junkie and general consumer of culture, I’ve sat through more Asian American shorts and features than I care to remember and practically all of them are forced to measure themselves besides Wang’s inaugural achievement. Most fail.

It’s not that there haven’t been other insightful, innovative or entertaining Asian American film works made over the last two decades, but few have mastered the secrets of subtlety that Wang brings to CHAN IS MISSING. Part of the problem lies in the nature of the subject – any film that attempts to answer the difficult questions of “who are we?” and “what does it mean to be an Asian American?” walks a dangerous path into didacticism.

However well-intentioned, many of the attempts that followed CHAN IS MISSING these past 20 years have either resulted in anemic, feel-good tales that celebrate multiculturalism without tackling the complexities of race and ethnicity seriously, or they reproduce the same narrow, troubled politics of cultural nationalism that have proven untenable as the community grows more diverse and disparate. What both sides lack is a politics and aesthetics of nuance.

This is precisely where CHAN IS MISSING has triumphed all these years. The film is ostensibly set up as a mystery, but the clues to solving it aren’t revealed in the main story arc but in the tangents. In one key scene set against the backdrop of the Golden Gate Bridge, Jo and Steve argue, Jo insisting that he understands Chan Hung’s difficulties in trying to assimilate as a Chinese immigrant into American society. Steve angrily retorts this is all old hat and yells at Jo, “this identity shit was ten years ago, fuck this identity shit…why are you tripping so hard off of this?” With this brief scene Wang manages to simultaneously summarize and predict 30 years worth of Asian American cultural politics yet absent of any heavy-handed brow-beating or liberal humanist hang-wringing.

It’s these many small touches that give CHAN IS MISSING its soul. It’s Peter Wang, dressed down in his Samurai Night Live t-shirt, singing “Fly Me to the Moon”; it’s the paranoid piano score that stalks Jo around Chinatown; it’s the overeager attorney who only speaks in legalese; it’s the faces of people at a bus stop. The film is filled with these seemingly random asides that become the heart of the movie

Chan is missing yet Chan is everywhere here. He’s a part of all the characters, a presence that infuses all the scenes. In the end, Jo remarks that this mystery goes unresolved as he shows us a picture of a hidden Chan Hung, silhouetted in the shadows. That we never find Chan nudges us to realize that he’s never meant to be found - he is, of course, an extended metaphor – a representation of Asian America as a complex, contradictory figure, impossible to pin down or stereotype. As such, to say “Chan is missing” isn’t a statement but a cipher, an open-ended riddle about our struggle to understand ourselves, our identities. But Wang never forces us to recognize this – it’s our conclusion to arrive at and what ultimately makes CHAN IS MISSING such a powerful film is how it understands and articulates that it’s not the final answer that matters, but our journey to find it.

Labels: chan is missing, review, Wayne Wang

<< Home